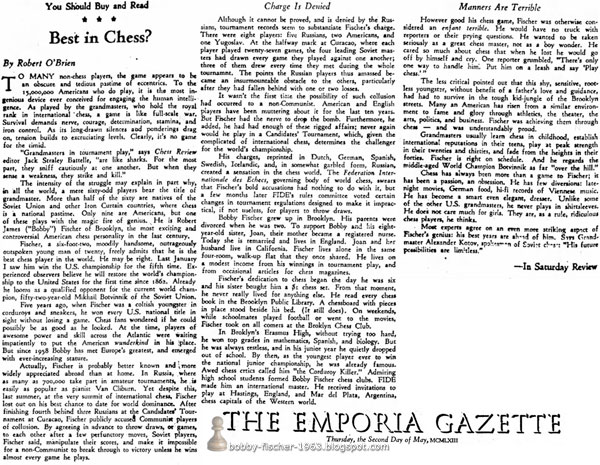

The Emporia Gazette Emporia, Kansas Thursday, May 02, 1963 - Page 3

Best in Chess?

To many non-chess players, the game appears to be an obscure and tedious pastime of eccentrics. To the 15,000,000 Americans who do play, it is the most ingenious device ever conceived for engaging the human intelligence. As played by the grandmasters, who hold the royal rank in international chess, a game is like full-scale war. Survival demands nerve, courage, determination, stamina, and iron control. As its long-drawn silences and pondering drag on, tension builds to excruciating levels. Clearly, it's no game for the timid.

“Grandmasters in tournament play,” says Chess Review editor Jack Straley Battelle, “are like sharks. For the most part, they sniff cautiously at one another. But when they sense a weakness, they strike and kill.”

The intensity of the struggle may explain in part why, in all the world, a mere sixty-odd players bear the title of grandmaster. More than half of the sixty are natives of the Soviet Union and other Iron Curtain countries, where chess is a national pastime. Only nine are Americans, but one of these plays with the magic fire of genius. He is Robert James (“Bobby”) Fischer of Brooklyn, the most exciting and controversial American chess personality in the last century.

Fischer, a six-foot-two, moodily handsome, outrageously outspoken young man of twenty, freely admits that he is the best chess player in the world. He may be right. Last January I saw him win the U.S. championship for the fifth time. Experienced observers believe he will restore the world's championship to the United States for the first time since 1862. Already he looms as a qualified opponent for the current world champion, fifty-two-year-old Mikhail Botvinnik of the Soviet Union.

Five years ago, when Fischer was a coltish youngster in corduroys and sneakers, he won every U.S. national title in sight without losing a game. Chess fans wondered if he could possibly be as good as he looked. At the time, players of awesome power and skill across the Atlantic were waiting impatiently to put the American wunderkind in his place. But since 1958 Bobby has met Europe's greatest, and emerged with ever-increasing stature.

Actually, Fischer is probably better known and more widely appreciated abroad than at home. In Russia, where as many as 700,000 take part in amateur tournaments, he is easily as popular as pianist Van Cliburn. Yet despite this, last summer, at the very summit of international chess, Fischer lost out on his best chance to date for world dominance. After finishing fourth behind three Russians at the Candidates' Tournament at Curacao, Fischer publicly accused Communist players of collusion. By agreeing in advance to throw draws, or games, to each other after a few perfunctory moves, Soviet players, Fischer said, manipulate their scores, and make it impossible for a non-Communist to break through to victory unless he wins almost every game he plays.

Charge Is Denied

Although it cannot be proved, and is denied by the Russians, tournament records seem to substantiate Fischer's charge. There were eight players: five Russians, two Americans, and one Yugoslav. At the halfway mark at Curacao, where each player played twenty-seven games, the four leading Soviet masters had drawn every game they played against one another; three of them drew every time they met during the whole tournament. The points the Russian players thus amassed became an insurmountable obstacle to the others, particularly after they had fallen behind with one or two losses.

It wasn't the first time the possibility of such collusion had occurred to a non-Communist. American and English players have been muttering about it for the last ten years. But Fischer had the nerve to drop the bomb. Furthermore, he added, he had had enough of these rigged affairs; never again would he play in a Candidates' Tournament, which, given the complicated of international chess, determines the challenger for the world's championship.

His charges, reprinted in Dutch, German, Spanish, Swedish, Icelandic, and, in somewhat garbled form, Russian, created a sensation in the chess world. The Federation Internationale des Echecs, governing body of world chess, swears that Fischer's bold accusations had nothing to do with it, but a few months later FIDE's rules committee voted certain changes in tournament regulations designed to make it impractical, if not useless, for players to throw draws.

Bobby Fischer grew up in Brooklyn. His parents were divorced when he was two. To support Bobby and his eight-year-old sister, Joan, their mother became a registered nurse. Today she is remarried and lives in England. Joan and her husband live in California. Fischer lives alone in the same four-room, walk-up flat that they once shared. He lives on a modest income from his winnings in tournament play, and from occasional articles for chess magazines.

Fischer's dedication to chess began the day he was six and his sister bought him a $1 chess set. From that moment, he never really lived for anything else. He read every chess book in the Brooklyn Public Library. A chessboard with pieces in place stood beside his bed. (It still does). On weekends, while schoolmates played football or went to the moves, Fischer took on all comers at the Brooklyn Chess Club.

In Brooklyn's Erasmus High, without trying too hard, he won top grades in mathematics, Spanish, and biology. But he was always restless, and in his junior year he quietly dropped out of school. By then, as the youngest player ever to win the national junior championship, he was already famous. Awed chess critics called him “the Corduroy Killer.” Admiring high school students formed Bobby Fischer chess clubs. FIDE made him an international master. He received invitations to play at Hastings, England, and Mar del Plata, Argentina, chess capitals of the Western world.

However good his chess game, Fischer was otherwise considered an enfant terrible. He would have no truck with reporters or their prying questions. He wanted to be taken seriously as a great chess master, not as a boy wonder. He cared so much about chess that when he lost he would go off by himself and cry. One reporter grumbled, “There's only one way to handle him. Put him on a leash and say ‘Play chess.’”

The less critical pointed out that this shy, sensitive, rootless youngster, without benefit of a father's love and guidance, had had to survive in the tough kid-jungle of the Brooklyn streets. Many an American has risen from a similar environment to fame and glory through athletics, the theater, the arts, politics, and business. Fischer was achieving them through chess — and was understandably proud.

Grandmasters usually learn chess in childhood, establish international reputations in their teens, play at peak strength in their twenties and thirties, and fade from the heights in their forties. Fischer is right on schedule. And he regards the middle-aged World Champion Botvinnik as far “over the hill.”

Chess has always been more than a game to Fischer; it has been a passion, an obsession. He has few diversions: late-night moves, German food, hi-fi records of Viennese music. He has become a smart even elegant, dresser. Unlike some of the other U.S. grandmasters, he never plays in shirtsleeves. He does not care much for girls. They are, as a rule, ridiculous chess players, he thinks.

Most experts agree on an even more striking aspect of Fischer's genius: his best years are ahead of him. Says Grandmaster Alexander Kotov, spokesman of Soviet chess: “His future possibilities are limitless.”

— In Saturday Review